Rehumanizing our visions for school

Systems change, new visions, equity, and how police reform and school reform are similar

**

This is a cleaned up and slightly edited transcript of an interview I did with Chris McNutt for the Human Restoration Project Podcast. The content was interesting enough to warrant sharing in a different medium (pun intended). You can listen to the podcast here.

**

Chris McNutt

Hello and welcome to Episode 79 of our podcast at Human Restoration Project. My name is Chris McNutt and I’m a high school digital media instructor from Ohio. Today, we’re joined by Dr. Erin Lynn Raab.

Erin is the co-founder of REENVISIONED, a movement to redefine the purpose of school. REENVISIONED aims to change the conversation of school away from standards, norms and improving the status quo and toward flourishing, justice, and thriving democracy. Erin and her co-founder, Nicole Hensel, both graduates of the Stanford Graduate School of Education, aim to collect 10,000 stories of students, teachers and community members to develop a shared vision of what school could and should be.

I’ve been working in education for almost 20 years. I started in international development, and worked both on Latin American programs for a large USAID-funded organization, and I spent a number of years in a township in South Africa, starting up a library and education center where I ran after school programs and leadership programs for young people. Then I worked with the National Department of Education in South Africa.

So I spent nearly a decade working all the way from on-the-ground with young people to huge international organizations and governments and kept coming back to this question of why it wasn’t working.

Etho and his father using the new KwaNdengezi Library & Education Centre

My kids weren’t leaving school empowered, oftentimes they didn’t even develop the basic literacy skills they needed to get jobs. But even more than that, they didn’t leave with the confidence or the understanding of the world to navigate their lives as adults.

At that time, I was still a little naive and I thought that there must be a group of experts somewhere who knew ‘the answer’ and all I needed to do is go find those experts and I could learn ‘the answer’ — a.k.a. the right way to do it. And then I would just go back out in the world and do it right. [laughs]

So I applied to do my Ph.D. in Education at Stanford. I arrived out at Stanford only to realize that, in many ways, that’s not what PhDs are for — solving big bold questions of practice. Often, they are largely training academics, researchers. So I ended up doing a very atypical PhD because I was there with this big question of, “why isn’t this working?”.

And this question of “why isn’t this working” is not just for a couple of kids but for many kids, maybe most of the kids across the world.

I had just started a library, so I thought, “well, I’ll start in literacy”. Literacy is necessary if not sufficient to living an empowered life.

I spent almost two years delving deeply into the literacy literature, only to find out that really smart people had thought about literacy for a very long time. We had empowering theories, we had empowering approaches…we just didn’t use them.

So then I thought, “well, maybe it’s in second language acquisition”. I really thought there must be something we didn’t know. My kids learned in Zulu, then they transitioned into English. And this happens all over the world. In Latin America the language of power is Spanish and children in indigenous communities have to transition into Spanish language of instruction. In the United States we have a huge number of English language learners because our language of power is English. At this time in my journey I though, “maybe it’s in this language of power, second language acquisition issue.”

So I spent another year and a half in in the second language acquisition literature, only to find out that really smart people have thought about second language acquisition for a really long time. We had empowering theories. We had empowering approaches. We just didn’t use them.

So I thought, “well, maybe it’s one of these newfangled areas like character development or social emotional learning that have gotten a lot of attention in the last few years.” I spent the next two years diving into those literatures only to find out that — not only were they *not* newfangled, we have literally been thinking about character development, Aristotle — but also we had great ways of thinking about them and doing them and we just don’t use them. In sum, I spent 4+ years reading deeply across a range of literatures with some of the most informed experts in the world…only to find that there wasn’t something “we didn’t know.”

We actually know a lot about how to foster both learning and community in our schools, and we just largely don’t do those things.

At this point, I thought, well, maybe education isn’t the area that I should be working. Maybe it’s not the social justice issue I thought —we know a lot about how to do it well and yet school might be actually harming the kids and adults in schools. We have high rates of depression, lots of dropping out, lack of motivation, lots of kids who we tell them they aren’t valuable because they’re not doing well on on exams. I really did a lot of soul searching.

And, luckily, at that point I also got introduced to systems theory. I started thinking, well, if it’s not going to be a new literacy approach or not going to be a new way of thinking about second language acquisition…

what would it take to shift or transform our system so that we can use what we already know?

I spent the last three years of my PhD thinking about what that means. What does it mean to transform a system…? That’s a very abstract thing. And then it’s a very concrete question of how to go about actually doing that.

One of the first things I found is that if you want to shift a system, you have to know what its purpose is and then you have to transform how people think about what that purpose is.

So REENVISIONED comes out of that first step of systems change — which is about changing what we see as the problem to be solved.

I truly believe we have capable, creative, well-intentioned, hardworking people at every single level of the schooling system.

You hear a lot of critiques of the humans at all levels — ‘it’s the superintendents, the educators, the parents, the kids’.

But we at REENVISIONED start with a foundational belief that there are really wonderful, hardworking, smart people working at every level of a system that inhibits their ability to actually do the right things.

This is at the root of what I see in Human Restoration Project as well— that ultimately schools are currently dehumanizing both for the adults and the young people in our system.

So alllll of that is to say that REENVISIONED, it came out of that journey. It’s not what I thought was going to come out of getting my Ph.D.. I kind of thought that coming out of my Ph.D. I’d be starting a new literacy program or literacy nonprofit or something along the lines of what I had done before. What I realized is that if I did that it would fundamentally leave a system intact that I felt was chewing up children.

So REENVISIONED is trying to change the conversation about schooling from one about competition, social mobility, Race to the Top, No Child Left Behind to one that is about human flourishing, democracy, and collective liberation. To a conversation about the questions of, “who are we as a community and how do we practice that way of being together in schools?”

Chris McNutt

Yeah, you you bring up that idea of systems thinking…

…and I’m with you. It’s very frustrating when there are education reformers who see teachers as if they’re dumb or ignorant or that they’re doing something wrong. I’ve seen, and I’m sure you’ve seen, that when you do change the conversation and you allow teachers to work within a different system, they do have a tendency to do the things we hope they would do instead. And that works out a lot better than blaming teachers.

All of us teachers feel stuck - for financial reasons, safety reasons, whatever it might be - upholding something that maybe we don’t agree with or maybe we just don’t realize it could be done differently.

There are so many people working to uphold the status quo through better teaching strategies or through marketing, at many points an “amazing professional development tool”, quote unquote, that costs a ton of money that might increase test scores by five percent or something without ever asking that fundamental question of, well, why do the test scores matter to begin with?

And why are we not focusing on things like motivation and agency, etc.? Especially when we have all of that research from literally hundreds of years to support that the things we’re currently doing don’t work? And there are other things that do work. Do you want to talk a little bit about what exactly it is that you’re doing to make this happen?

Dr. Raab

Yes, I do, but I would love to just say one thing on what you just said, which is one of the things you learn when you start really delving into systems thinking —

whenever you have patterned or similar responses by individuals across different contexts, you’re facing a systems issue, not a problem with individuals.

Does that make sense?

So, you think about schooling, whether it’s in our high income schools where across the country we have really high rates of anxiety, depression, suicide, or in our low-income schools where across the country we have high rates of disengagement, demotivation, dropping out. Principals across the country are like to be most effective in their fifth year, but around 50 percent of them leave by their third year. Patterned responses across different contexts…

We are facing systems issues but we tend to blame individuals and create interventions for individuals.

For instance, I lived in Palo Alto, CA for a long time. There is a really big anxiety and depression and suicide problem in the area.

And adults there say, “We have to support these kids — why don’t we hire more therapists?” That’s really important — we do need to support these kids. But it’s also just triage.

It’s really important to those particular students to get the help they need, but unless you change the system, you’re going to end up continuing to need that triage every year with each new cohort of students.

The same thing applies when we look at adults. We continue to blame adults and especially to blame educators for their behaviors. And yet when those behaviors are consistent and seen in almost every school — when the anomaly is healthy behavior - then we know that the actions of individuals are driven by the way we created the context, not by those individuals.

We can see that it takes a kind of super-human strength or motivation by educators to overcome or be outside of that that patterned response cued by the environment.

So one of the biggest keys to real change, to systems change, is asking how we might design those environments differently so that most people naturally act differently…rather than trying to change each individual.

Chris McNutt

Exactly. That actually reminds me of a conversation I was just having with Nick the other day where we were talking about how right now the the main zeitgeist topic is police reform . And I was reading The End of Policing by Alex Vitale. It talks about why traditional police reform measures don’t work — programs like anti-bias training, teaching people to shoot someone at a different spot instead of a shot that kills them, etc.. Instead we could be talking reforms like reallocating their budget, I guess what many people are calling defunding the police budget, because this tends to work better because the system itself has changed.

Then you’re talking about this idea, systems based thinking, and applying it to education — because there is a carceral component to education. I mean, there are, quote unquote, “bad teachers.” But that’s not really the overall problem right now. The problem is that teachers are upholding a system that doesn’t work. So it’s the exact same way as there are some bad cops that do bad things but, that’s not the core problem. In general, there are a lot of things that police do they shouldn’t be doing to begin with — it’s not their job to address mental illness or breakdown, etc., which is the exact same way with teaching — it’s not teachers’ jobs to do many of the things they do.

If you’re upholding a system where my goal is to check off a few boxes and increase test scores by 10 percent then the likely point A to B to C of getting there is going to be way different than if I set up the system to be, “I want students to recognize or at least get on a path to purpose and what does that look like for me?” The conversation entirely changes and there will still be, quote unquote, “bad teachers,” but it’s going to be way easier to identify that that going on in that system as opposed to what’s going on currently.

Dr. Raab

Yeah, and in that instance even what it means to be a bad teacher changes. It changes from someone who didn’t get the message across to someone who maybe isn’t treating their their students as humans or creating the right kind of community.

I think that’s a really apt analogy between the movement for police reform and how we might change how we think about education reform too.

One of the things that really worries me about the conversation right now about policing is the demonizing of cops — of the individual police officers. It doesn’t bode well.

Think again about how we know what a systems issue vs a symptoms issue is: when there are patterned responses across contexts. We have a systemic racism problem. The key word in there for finding solutions is “systemic”. The more that we can look at the ways behaviors are shaped by environment and culture, and then change the environments and cultures, the more likely we are to make true change in a positive direction.

It doesn’t mean that individual people don’t make bad choices, that there aren’t some bad educators or some bad cops… but when you have patterned behaviors, the problem is not about those individuals it’s about an environment and culture that allows those behaviors to thrive and spread.

Furthermore, I think

the more that we shame people the less likely they are to to transform.

I think we’ve seen this in education as well. As soon as you’re starting to publish educator names and shame them for not getting the test score growth rate in newspapers, the less able educators are able to take the risks or orient towards learning and the ways that they need to take action because their identities are so under under threat already. And I worry a little bit that we’re doing the same thing with the police at the moment.

Chris McNutt

Yeah, yeah. This is going to go on a tangent here for a little bit, but I really like this mode of discussion. So I think that something that REENVISIONED aims to do is stop this, what I would see as like a neoliberal co-opting of what’s going on in education for the — since like the 70s or 80s, but really long before that, we see all these things that don’t work in education. Instead of changing that conversation, we tend to use the right words to talk about reform. So I’ll talk about like I want all students “to achieve,” quote unquote. But we never define what that word achieve means. And when certain individuals do very well in that system, as in their students, let’s say, get a scholarship to Stanford or something like that, we uphold those teachers as proof that the education system works, which this can be seen in any system in the United States.

If we only highlight those individuals doing well or those individuals doing poor, no one’s ever questioning, “Ok, well, what does the system need to do?” Well, and if we change that system, does that mean that those students are still not doing well? Like, are we taking something away from someone? And the conversation just drives down to this question about individual people’s actions as opposed to a collective action.

Dr. Raab

Chris, I love that. I don’t think that this is going off in a random direction at all — I think this is actually central to the point.

And I would agree with you. One, I think it’s interesting that, just as how we think about what capitalism is has changed over time, we have also changed how we think about the purpose of schooling.

My master’s degree was in development studies, which means I studied how we thought about what it means to develop as a country. And that has changed over time. What it means to “be developed” and also what it means to be “capitalist” or “democratic.”

Similarly, when public schooling started in the 1800s, we were heading into civil war as a country. It wasn’t clear that this democratic project of ours as a relatively new country was going to work. We were incredibly divided and there was a decline of other socializing institutions, like churches. And so schooling arose as a way to socialize us into being citizens.

Basically, we think about it like it’s for learning and it was established to teach children content, but — I might get the statistic a little bit wrong here - but on the East Coast, we already had about a 90 percent literacy rate. It was something astonishingly high.

We think school was to make sure that all kids learn to read from an early age and prepare them for work. But that was not the original narrative with Horace Mann. Horace Mann used a couple different narratives, but his primary motivation was that we need a way to create a sense of who we are, as Americans.

School was to create a “we”, both within local communities — to make sure that local communities were working together democratically and thinking about the growth of their young people. But then also as a nation — what does it mean to be American in a time when we had such huge divisions?

Which is interesting when you when you think about our divisions today. Then, we got through the Civil War….I’m going to do a very brief history :) We entered a period of industrialization and suddenly the divisions weren’t the most salient issue. Instead, we needed a way of thinking about how to prepare workers. But it was still very much a collective frame about the purpose of school. A social efficiency purpose.

Think about when the Russians launched Sputnik. We didn’t say you should study science because that’s where all the money is, which is what we say today. We say be a scientist or be an engineer because then you can make good money. No, in the 1950s we said, “study science so you can help your country succeed.” The narrative around education from the late 1800s through the late 1970s early 1980s was really about these this idea of serving the larger national good. That’s why you study. That’s why you went through school.

Then in the 1980s it started shifting. Think, even with the famous report A Nation at Risk… if you read A Nation at Risk it’s still very much in the social efficiency frame. It says we should invest in in education because we’re going to fall behind all of these other countries in our economic growth. The argument wasn’t that these kids over here aren’t going to have the same kind of access to social mobility that these other more privileged kids have. It was social efficiency until

But with the fall of the Soviet Union we emerged as “victorious” and we started taking on the very neoliberal framing of the individual as the key to change and freedom. That each individual should be able to navigate the system.

Equity changed from everyone having a chance to be part of this national project to everyone having a chance to compete.

In the individual efficiency frame that has dominated since then equity seems to be framed as, “does everyone have an equal chance to end up in the top one percent?”

We discuss how to equalize competition and we are not discussing whether or not we should even have such a disparity between our top one percent and the rest of us. We’ve implicitly decided that equality is whether we have a really diverse representation in our highest class. And I think that’s really undermined our ability to serve all children in our education system. I mean, it’s muddled the question. It’s not the right purpose for schooling — competition.

Schools don’t make socioeconomic policy. Governments make socioeconomic policy. We [teachers] can’t solve economic inequality. True educational equity isn’t about leveling the playing field, it’s about changing the game.

One of my favorite philosophers, Randall Curren, he talks about how

people can be making very individually rational decisions that are collectively irrational.

In one school over here, you can work to maximize your test scores. You can get all of your kids into the top universities, etc. But if you’re looking at building a system, all that “success” in the one school means is that some kids down the road don’t have that.

So you’ve created a situation in this competitive game where you always have some people who are “successful” and others who aren’t. Then, you’re blaming the kids who don’t achieve that success. You’re blaming the the bottom 50 percent for being in the bottom 50 percent. And yet what we’ve done is we’ve created a situation in which somebody has to be in the bottom. I mean, mathematically, obviously somebody has to be in the bottom 50 percent — but what that means changes dramatically.

Once you can really see that you can see it is lunacy.

It’s lunacy what we’re doing.

We’re constantly studying kids at the bottom, studying the people at the top. How do we make sure the people at the bottom can get to the top? What’s special about the kids at the top and how do we make kids at the bottom like that? And it’s like a whack-a-mole game at the systems level.

We won’t have equity unless we change how it is we think about what we’re doing. We won’t ever achieve equity unless we pursue true educational equity rather than pursuing ability to compete as equity.

True educational equity asks,

“Does every child have an educational environment that is rich for learning, in which they are seen valued, have the resources they need and the humans they need to to grow and learn and community?”

You can do that for every single student in the United States, every single one.

You cannot make sure every single student gets into Stanford right now. Schools cannot make sure every student has a well-paying job someday. That’s not something schools can do it. If we create an economic system in which 40 percent of people don’t earn a living wage then 40 percent of students are going to graduate and not earn a living wage. Whether or not they’ve learned differential calculus or gotten a Ph.D., that’s not a problem that schools can solve.

Does that make sense?

Chris McNutt

I think what you’re saying makes perfect sense. What I think about, too, is the idea that we can then rationalize inequity or rationalize our practices. I find myself doing this all the time where I’m looking at a grade book, which is just like a bunch of zeros and ones, and then it just mindlessly going through like that’s a zero. That’s a zero. That’s a zero.

And, subconsciously, what I’m doing is I’m saying these kids are worth something and these kids aren’t.

It allows us as a society, both the students in the room, sadly, as well as the teacher, to start to frame it as, “well, those students deserve to not have as good of a life as the students who are doing these things right.” Those that are following what it is I’m telling them to do are worth more.

Which could lead to a whole separate discussion of whether we are basically training a entire generation of people to believe you shouldn’t question authority, that you should just do what you’re told. And to believe that those who are the rule abiders, those that have done this very particular area of study, are more worthwhile than those who haven’t, which by itself is a giant equity issue..it’s a crazy thing.

And I know that builds into your discussion of what it means to have a good life too. The first thing I think of when I think of that question is Alfie Kohn. How he introduces most of his talks by asking groups of teachers, parents, about what it means to have a good life. And when he asks the question like, what do you want your child to be like when they’re 30? They always say, like, “happy, loved, content, just very happy go lucky, happy times”. They don’t say, I want them to be rich or quote unquote “successful” in economic terms. But yet that’s the entire framing of how schools typically works: “I want you to get an A so you get into a good college so you get a good career, etc..”

Dr. Raab

Yes. I love that and it’s so similar to what we do. I promise we will get to what REENVISIONED actually does. And part of that is catalyzing conversations about the exact questions you’re talking about.

So, both in my dissertation research and then with REENVISIONED, part of what we do is create space and catalyze conversations between young people, between young people and adults, and between people working within the particular system or community. The conversations are about what it is ultimately we hope for our lives, and for the lives of the kids we care about.

It can be too big and broad to ask what we want for other people’s children, but when you think about a kid that you care about it gets real. What is it you want for them when they’re in their thirties? What is a good life?

And, you’re right - it’s not that people don’t want their kids to earn money someday, or that they don’t care about material wealth. In fact, one of the things that surprised me in my research was that wealthy parents were just as likely as less wealthy parents to say that they didn’t want their kid living on their couch when they are 30.

But people care about money partly because we’ve created a system in which there are real material consequences, real physiological consequences, and real health consequences to ending up at the bottom of our socioeconomic system. So people feel fearful about it. I would say they’re justified in that fear.

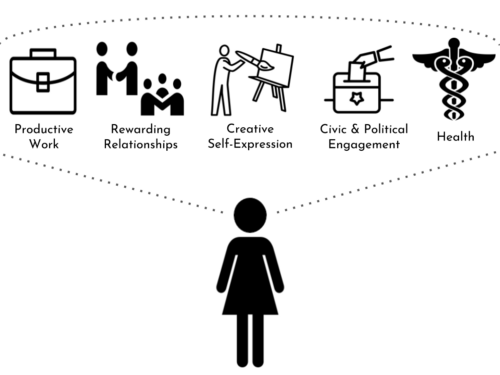

But a good life is bigger than that. We found that when people talked about kids they cared about there were five main parts of a good life.

Productive work — so work that didn’t kill their soul but paid the bills;

Rewarding relationships - So they wanted them to have interpersonal, one on one, relationship but also belong to a larger community, be part of a group;

Self-expression — to creatively express themselves, have a sense of who they are and be developing that solid sense of self over time;

Civic engagement — they wanted them to be civically and politically engaged, and that didn’t necessarily mean voting. Right now we think of this as meaning a particular thing, particularly as we’re heading into this election. But actually this is more than just voting - people saw this more in line with what Hannah Arendt called world-making. “How do you work with others to create the world that you live in?” And that might be through Rotary, that might be volunteering with a local garden. But how is it that you come together with others in your community to make your world

Health - everyone wanted kids they care about to be physically and mentally healthy.

So, then, part of what came out of this is the next question, which is, “OK, what is the relationship then between what happens in school and that future good life?”

And one of the things to note is that those categories are really broad — what productive work looks like for one person and what they enjoy is really different than it might be for another person. I had one little girl who really wanted to be an Olympic horseback rider, and I had one little boy who really wanted to be a robotics engineer. I personally have not thought about either of those careers realistically.

So what matters is how well you can see the options available to you and how well you can make choices between those options in a way that is meaningful for you.

So, for another example — good relationships can look different. Some people like to have three good friends. They are good friends with them their whole life and they’d rather just not really interact with too many other people. They get all their needs met through those three friends. I love to know everybody. I love people. I choose to know and build relationships with many people. Our choices are different based on our preferences and what’s meaningful and fulfilling to us.

So within those categories a ‘good life’ is going to look really different. A big part of flourishing, then, is how we make decisions about these different aspects of our lives. When I think about flourishing, I draw on Aristotle, who thought about about flourishing as being when we can make informed decisions about our lives. He called it deliberative action, but flourishing, or eudaimonia, is about how we can make informed decisions about our lives according to our own values, skills, strengths and interests.

I think one of the things that struck me about his writing so many years ago is that he already identified that to be able to do that, to be able to flourish, you need two prerequisites fulfilled that are beyond your control. First, you need to live in a society in which you have the freedom to make choices about yor life. Second, your basic needs have to be met — because if your basic needs aren’t met all of your choices are oriented towards meeting those basic needs. And that’s not that’s not real flourishing. That’s not real freedom.

There’s been a lot of research in the last 30 to 40 years by Martin Seligman and others around around what it means to flourish from a social psychological lens. What it adds to Aristotle, I think, is that you can then say

a person really flourishes when their core needs are met, when they have the freedom to make choices about their lives and when they find their choices to be meaningful and fulfilling.

That’s what social psychology really adds to the discussion- do we ultimately make the choices that we find meaningful and fulfilling? The role of school in all of this is multiple.

School helps us know ourselves, it helps us practice making choices, and it shapes how we see the choices that are available to us in the world.

So it develops our sense of ourselves and the world. It allows for a sense of our place in the world, what options are available to us and, most importantly, it can allow us to be in a place where we can practice having the freedom to make choices about our lives and test out whether we find them meaningful and fulfilling.

I’m getting little bit abstract again, and obviously this is a bit ideal rather than actual school. But

what we know from neuroscience and what we know from Aristotle - from ancient philosophy - now clearly aligns:

who we practice being we become.

Literally in our brains when we do something or think something many times it strengthens the synapses and it makes it more likely that we do that thing or feel that thing again. We make physical structures in our brains as we practice things. Literally who we practice and how we practice being is who we become. And Aristotle said the same thing. It’s so fascinating.

And so when I think about school, I wonder, how are we practicing we we want our kids to become? How are we practicing that flourishing now? The way we are most likely to make sure our kids flourish in the future is if they practice flourishing now. The way we’re going to make sure that they are able to be collaborative and creative and work with others and build healthy communities and healthy relationships, is whether they’re practicing that today. Whether they are learning how to do all of those things and making those brain structure.

So, I think we shouldn’t be surprised if, when we haven’t practiced those things, if we practice competition and scarcity and inequity, then I don’t think we should be surprised when that’s what is showing up in our political institutions and our companies once children are out of school and in the world.

Chris McNutt

It really highlights, I think, the appeal if not necessarily the end goal, but the appeal of books like Tony Wagner’s work or Ted Dintersmith’s, where there’s a big focus on educational reform for 21st century skills. I think most people agree with the concept of something like, “there should be more creativity, we should have more choice, or these skills are very important”. But where the alignment may be off between educators and outside interests like those is the assumed purpose there is that we want really well-equipped workers as opposed to we want people people who, as you’re describing, are flourishing. Maybe a student’s goal is they want to have a really well-paying job, but it doesn’t have to be. There are many different ways you could go with those skills.

And, as you’re saying, when you have an education system that is, “listen, obey and answer,” it shouldn’t be surprising that you have political institutions that basically don’t listen to you.

No matter what side you’re on, people feel like they do not have a voice. Well, they’re used to it. They were basically trained or brought up in an environment where there was very little choice — that was the practice.

To build a democratic classroom means you surrender some of that power as an educator so that students have the opportunity to make those choices and to act in that environment. So that someday it’s not just that they have the ability to choose the next thing that they’re going to work on for their employer, but that they can deconstruct the power narrative altogether. So it’s my choice who I work for and how I work for them or who I vote for, who I rally for.

I think that that pedagogical difference is really important to identify early on so that we’re not just shifting from basically a system where we focus on content, the skills to obey someone else, but to transfer from content acquisition to the skills to make choices for ourselves and those individuals.

Dr. Raab

One of the courses I taught at Stanford was the History of School Reform with David Labaree, who is a legend. I highly recommend his book, Someone Has to Fail if anyone wants a good overview of of the last 180 years of school reform — it’s excellent. Much of the last 180 years has been, “so much reform, so little change”.

But in the way that you’re talking about, I think

there are three main places, strategic places, that reformers go wrong right off the bat.

The first way reformers go wrong is they misdiagnose the purpose of school and thus the problem of school.

What I found is that there are four main ways we talk about what the purpose of school is. I’m talking all the way back from Plato’s Republic to now when we talk or write or research school we have four different frames for the purpose of school.

Individual Possibility: We talk about it as being for individual human development, SEL, “learning,” etc.. So “how do I develop these kids’ math skills? How do we develop social emotional learning skills? Whatever it is, individual learning, and development.

Social Possibility: We have ways of talking about how we develop who we are. Socializing us into a shared larger identity. So, the citizenship, not just skills, but the orientation, the practice of the sense of identity, of being part of a collective.

Social Efficiency: A third way we talk about it is the social efficiency way of how do we prepare workers. How do we make sure we have enough STEM workers? How do we make sure our economy can compete with China’s? These kinds of questions, lots of political scientists and lots of economists and lots of policymakers frame their thinking and their research and their policy in social efficiency.

Individual Efficiency: So, how do we make sure individual kids can navigate the schooling and socio-economic systen. How do I make sure my kid gets into Stanford? How do we make sure every kid graduates from high school? These kinds of things.

Raab 2017 — Four Purposes of Schooling

Now, these four purposes are just true — I think that they’re just true. They are just a description — we have those four purposes for schooling. But when we think about the design of actually what happens within schools every day, what I found is that you have to design for the individual and collective development purposes, not for the efficiency purposes. When you design for the development, the possibility purposes, you also fulfill the efficiency purposes. When you design for creativity and learning and community, it turns out people are prepared to take different kinds of jobs, for instance.

But if you try and design for getting people into the jobs, I mean, it’s like planned economies. You know, it’s too complex. It’s not the way humans work. You end up dehumanizing schools as you try to shape people to fit the slots available in the economy.

This is not an engineering exercise, this is this is a cultivation exercise, both at the micro level and at the end. So the first thing is that they frame it incorrectly. They think about the problem we’re solving incorrectly.

The second way reformers go wrong is that they don’t understand the connection between student experience now and future outcomes well.

Or rather they think about it incorrectly. The best way I have come to think about this is through a metaphor. So lots of people think about this as an engineering or as a manufacturing problem: “Oh, what we need are these kinds of people in the world” — and then they try to design a linear process to get there.

Whether that “there” is even Democratic citizens or STEM workers or or flourishing any, any of it — you can actually take the right problem and still think about the connection between school and those future outcomes incorrectly. Lots of people have changed their thinking to be talking about flourishing, but how they think about getting there is they backwards plan all the way from pre-K exactly what curricula and knowledge they’re going to tick off along the way so that they have this nice continuum.

There are a couple of obvious things wrong with that aren’t intuitive — but once you see them you can’t unsee them. One, growth, human growth, is not linear. I mean, any of us who pay attention to our own growth know that growth and learning happen over the long term and it’s not linear. You can’t go back and say learning is going to happen in this very consistent way over 18, 26, or 84 years. That’s just not the way learning or growth works. We grow a little today, then a lot next week, then we tread water for a bit, then we regress, then grow again.

Two, the next non-intuitive thing is that school is not about fixing kids. People think, like, “oh, we’ve got to make them creative, we’ve got to intervene to make sure that they have grit”. But kids are already all of these things! They just need the right environment and experiences for them to grow.Just like an acorn already has an oak tree inside of it, you only have to create the right environment for growth or creativity or persistence — kids already have all of those things inside of them, they just need opportunities to practice them.

We don’t need to fix kids. We need to create an environment in which they have the opportunity to be who they are and practice being who we hope they will become.

The third way reformers go wrong is that they misunderstand that teachers can’t control the outcomes directly.

And this should be so obvious. It’s one of those simple, obvious truth that that somehow gets lost in our conversations. But whether you’re talking about test scores or whether you’re talking about a really healthy human being who is flourishing, none of us have direct control over someone else’s growth. It is always an interaction between an individual and their environment. Because people have will, because each person is different and interprets the environment and experiences differently.

What educators have control over is the environment that they design and the set of experiences that they design for young people, not the ultimate outcomes. I think of this in the same way that that a gardener might think about the soil and the sun and the water and how that might be different for each plant, but they can’t control whether or not that particular tomato comes out exactly how they predicted. This doesn’t mean the don’t heavily influence the outcome — they can overall create a very thriving garden if they’re paying attention to to the environmental factors, the things that are within their control.

So the third way that that reformers often go wrong is that they think they can directly control the outcomes if they just put the curriculum in exactly the right order. You know, if they if I think about it like the manufacturing line, if we just intervene here and we add that that little piece, you know, that will end up a product.

I find it so funny when schools start requiring coding classes and think that all of a sudden we’re going to have all these STEM-interested kids, which doesn’t happen — it just makes kids hate coding, which is very ironic.

Also what I always find interesting about this drive to create equity by having more women and people of color who become STEM workers or coders is that, let’s be honest that once women and people of color are the primary coders, that job is just not going to be paid as much. I mean, we’ve seen that again and again and again that that is not the way to create equity.

Chris McNutt

Yes.

Let’s dive into the the practical. We got the theoretical. I’m really into it, like everything you’re talking about is directly in line with what HRP does, the whole shtick for us is this. I get it. Let’s talk about how people can get involved with REENVISIONED and how this could be incorporated maybe in a pandemic context, how could we use these resources to make something happen?

Dr. Raab

OK, so REENVISIONED does three things.

One, we very literally catalyze new conversations in communities.

We have a whole project that we’ve developed that that is youth-centered. Young people interview each other and interview adults in their lives. They’re the ones who learn to qualitatively code and so they’re the ones to make sense of that data.They pull out the themes and they come up with a vision for their for their classroom, for their school, for the district.

Students presenting the themes from their interviews with community members.

We’ve adapted this process to do it in many different ways and have piloted it across five states. We’ve used this with adults at a huge national network where actually the adults are the ones still asking the questions and making sense. And we’ve used this on a micro level in one classroom. For instance in an alternative high school in California classroom where this one class of students interviewed people across the whole school. The process can be done if you have a one day in a long workshop or it can be done over the course of an entire school year. So it’s just really, really flexible.

We’ve created a process for asking these different kinds of beautiful, important questions together.

And I think it’s really important that it involves both young people and adults. I think a lot about how adults, elders, can bring wisdom — we’ve lived through things, we’ve seen things. And young people bring renewal — they bring creativity, they bring new perspectives. And so bringing those two together is really, really important.

So we have a set of resources to help people catalyze these important conversations in their school communities.

The resources to catalyze these conversations are free and they are online (here).

They are not beautifully designed yet. They’re still all just in PDF and Word. But all you need to go is go to the website — www.reenvisioned.org — and put in your email. You can download all of them for free.

If it seems like something you want to do and you want to partner with us to think about how to make that process work in your classroom or in your district or in your school, then just reach out and we’d love to work with you.

And so that is one way people can get involved — if you’re an educator or school leader and you want to think about how you have these conversations as a community, we have a bunch of resources for you.

The number two thing we do is we’re building a network of like-minded people.

Some of the people interviewed or involved with REENVISIONED at the start. Check out interviews at www.reenvisioned.org.

This is how we met, Chris! I reach out to and meet leaders across the country. We do interviews and networking calls and try to learn about who is out there in the world doing work that is aligned with ours. If you just want to talk, reach out. I talk to probably five to seven educators and school leaders eacj week trying to learn what’s happening and understand new perspectives.

Part of growing a network is doing consulting work with like-minded organizations, nonprofits and schools who are thinking in aligned ways. We help them with impact strategy and organizational strategy and evaluation and leadership development. And, part of our work has come up with a set of design principles for creating empowering environments and experiences — so we work with educators and nonprofits around program design. When you think about “how do I create that garden?”, we have a set of design principles for approaching empowering program design.

We also have a book club, a monthly book club for the past few years where educators and nonprofit leaders from across the country get together to discuss education and education-adjacent books. Next month we’re reading Abolitionist Teaching by Dr. Love. So, if you’re interested in being part of a really wonderful community of educators who are thinking deeply about these topics and committed to their own learning monthly, reach out - we’d love to have you.

Also, we have some of the social media — a Facebook community and Instagram community, and we’re on Twitter. These different social media things…which, honestly, I’m not personally that great at, but I think are really important for getting the word out.

The number three thing we do is thought leadership.

You know, a lot of what we’re talking about is a weird shift in frame from how we usually talk about what needs to happen for schools to change. It actually is a radically different way of thinking about what it is that we’re doing through school, what school is for and how we can go about doing that well, and so we’ve been focusing on writing and sharing ideas.

My dissertation, “Why School? A Systems Perspective on Creating Schooling for Individual Flourishing and a Thriving Democratic Society,” is out there, which is probably the most comprehensive piece. But we do blog posts trying to illuminate the different facets of the shifts in thinking that are needed. We talk about the mindset or framing needed to be able to see the systems problems clearly and how we can solve them in ways that are aligned with this

vision of creating a strong, thriving democracy and a place where all young people and all educators can be flourishing both today and and in the future.

So, 1) we catalyze conversations; 2) we’re building a network of like-minded educators and leaders; and, 3) we’re engaged in thought leadership to get these ideas out there.

Chris McNutt

Human Restoration Project — www.humanrestorationproject.org

Great.

I hope this conversation leaves you inspired and ready to push the progressive envelope of education, you can learn more about progressive education, support our cause, and stay tuned to this podcast and other updates on our website at HumanRestorationProject.org. You can learn more about REENVISIONED at www.reenvisioned.org.